Police Harassment

2014-07-07

I've been hassled by the police several times in the last month. Their behavior makes me sick, and I hope they stop, but what can you do when people in power are power tripping at your expense? I suppose you take pictures and video and expose their actions as a pathetic excuse for the job they are supposed to be doing.

May Twenty-ninth

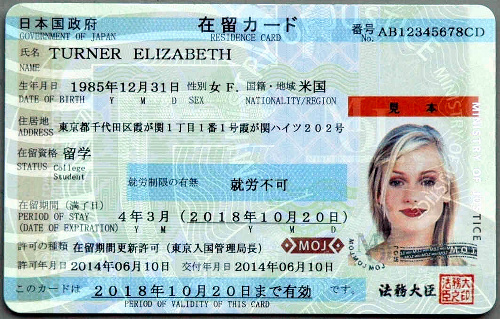

The other day, the police asked to see my Residence Card, which is a form of official documentation that foreigners carry when in Japan. It is generally accepted that the law states I should carry either the card with me, though my passport might be an acceptable alternative. Since the Residence Card is carried exclusively by foreigners, and since Japanese citizens are under no obligation to show ID on demand, the policy of asking to see foreigners' identification is openly discriminatory.

Letter to the Police

Here is a letter I sent to the Musashino City Police Station (武蔵野警察署) on June 8th.

武蔵野警察署の方へ

Dear Musashino City Police,

先日武蔵境駅前、警察官2人は私に声をかけました。その2人は優しかったです。私に「在留カードを見せてください。」と言いました。約3分くらいを話して、そして私は在留カードを見せました。その2人は「ありがとうございました。」と言って挨拶して、どこかへ行きました。

The other day, I was approached by two police officers near Musashisakai Station. They were friendly. They asked me to show them my Residence Card. After 3 minutes of talking, I showed them my card. They said “Thank you” and went away.

法律として外国人は在留カードを持つべきだと思います。

The law states foreigners must carry their Residence Card, I believe.

ただ、「在留カードを持つこと」と「在留カードを見せること」は同じではありません。

However, carrying the Residence Card and showing the Residence Card are not the same thing.

質問はいくつあります。警察官に「在留カードを見せてください。」と言われる時に、私は見せる必要がありますか?これは法律のどこで書いていますか?お断ることは犯罪ですか?例えば、お断ったら、どうなりますか?

I have some questions. Is it required that I show my Residence Card to police when they ask? What law states this? Hypothetically, if I refuse, am I committing a crime? What will happen?

もちろん法律を守るつもりです。

Of course I will obey the law.

どうか説明してもらえませんか。よろしくお願いします。

Thank you for any information you can provide.

What I Didn't Say

In the interest of getting answers, there are some things I didn't write in the letter. I didn't write that these ID card checks are racist. First of all, they're based on the premise that you can recognize a foreigner by their appearance, which means the ID checks target all visible minorities, which includes Japanese citizens who "look foreign" and excludes non-citizens who "look Japanese". Second of all, the ID check only applies to foreigners, which means that other people seeing the ID check happen jump to the conclusion that foreigners are dangerous, because the police feel the need to question us so often. That assumption is not precisely the police's fault, though certainly they have an obligation to educate the public in situations like this where their actions create a misunderstanding. Just as importantly, foreigners are less likely to commit crimes in Japan than are Japanese citizens. If the police want to target a group because they're worried the group is criminally inclined, one could argue that it should target Japanese citizens ... except that this kind of thinking is absurd.

Ken Tanaka of OWJ News gives us some information about crimes by foreigners in 2013.

Crimes by foreign visitors in Japan increased for the first time in nine years in 2013, the National Police Agency said Thursday. The number of foreigners who faced criminal charges in 2013, excluding those with permanent resident status and related to U.S. forces in Japan, totaled 9,884, up 735, or 8 pct, from the previous year, the agency said. Of the total, 4,047 were Chinese, followed by 1,118 Vietnamese and 936 South Koreans.

Note that the majority of these crimes were committed by people from countries that stereotypically "look Asian" and are therefore unlikely to face ID checks. The number of Chinese and South Korean residents in Japan is relatively high, so it is unsurprising that those countries are clearly represented in the above totals. Let's see what Debito writing for the Japan Times has to say about crimes by non-Japanese.

A decade ago [2003], the NPA could make a stronger case because NJ crimes were going up. However, as we pointed out then, Japanese crimes were going up too. And, in terms of absolute numbers and proportion of population, NJ crimes were miniscule.... Yet neither the NPA, nor the Japanese media parroting their semiannual reports, have ever compared Japanese and NJ crime, or put them on the same chart for a sense of scale.

An ID Check Video

If you're interested in seeing what it looks like when the cops ID you, here it is. If you live in Japan, it's worth your time to watch these kinds of videos so that when the cops start talking to you, you know what kinds of things they're going to say. This can help you remain calm when authority figures start asking for ID and are vague about whether you actually need to present it.

Police Department's Reply

Here is the Musashino Police Department's response to my inquiry, along with some 2009 official translations and some parts — those revised after 2009 — translated by me. The first half of the letter deals with exactly when and where I am legally required to carry and show my Residence Card.

| 日本語 | English |

|---|---|

| 1 法律的根拠 | 1. Legal Basis |

| 出入国管理及び難民認定法(抄) | Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act |

| 条文・第二三条第2項 | Article 23 Paragraph 2 |

| (内容) | (Contents) |

| 中長期在留者は、法務大臣が交付し、又は市町村の長が返還する在留カードを受領し、常にこれを携帯していなければならない。 | Medium and long-term residents are to keep on hand their official Ministry of Justice-issued identification, such as a Residence Card. |

| 条文・第二三条第3項 | Article 23 Paragraph 3 |

| (内容) | (Contents) |

| 前二項の外国人は、入国審査官、入国警備官、警察官、海上保安官その他法務省令で定める国又は地方公共団体の職員が、その職務の執行に当たり、これらの規定に規定する旅券、乗員手帳、許可書又は在留カード(以下この条において「旅券等」という。)の提示を求めたときは、これを提示しなければならない。 | Foreigners described in above Paragraph 2 must present, when demanded by immigration officers, customs officers, police, maritime peace officers, or others as declared by the Ministry of Justice, or other employees of local public government bodies, as part of executing their professional duties and as stipulated by this regulation, their passport, crew identification card, permit, or Residence Card. |

Punishment

The second half of the letter details the punishment. There is no need to translate it verbatim, because it's unambiguous. If you violate the above law, you can be imprisoned for up to a year and fined up to ¥200,000 ($2000). The fine is largely irrelevant, because if you're found guilty of violating that law, the chances of keeping or renewing your work visa drop considerably. I don't believe the Japanese government would try to put an American in prison for several months merely for not carrying an ID card around when they could avoid the international pressure by instead throwing that person out of the country. Either way, it'd be an ugly situation, one much better avoided.

Unanswered Questions

The law says I need to carry my Residence Card, and that I need to show it to police when they demand it, but only as part of executing their professional duties and as stipulated by regulation. What professional duty stipulate that the police can demand my ID when I'm walking through a train station? I do not know. Maybe one exists, or maybe not. None of the police that I've asked, including the person who wrote the above letter, have bothered to include that one piece of crucial information.

Another Letter

In the final line of the above passage, we see that the police can require I show my Residence Card, but only as "part of executing their professional duties". In an effort to determine what they think those duties are, I drafted a second letter to the Musashino Police Department.

武蔵野警察署の中山祐二様へ

Dear Mr. Yuji Nakayama of the Musashino Police Department,

先日の手紙ありがとうございます。

Thank you for your letter the other day.

その手紙には、中山さんは出入国管理及び難民認定法の条文・第二三条第2項~3項の説明をしました。説明してありがとうございます。

In your letter, you explained about the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act, Article 23 Paragraph 2 and 3. Thank you for the explanation.

私は質問がもう一つあります。3項の中には「その職務の執行に当たり」という発言があります。武蔵野警察署の警察官は駅前で在留カードチェックの仕事に関しては「その職務の執行に当たり」って何ですか?これは法律のどこで書いていますか?

I have an additional question. In Paragraph 3, there is some language about, "... as part of executing their professional duties ..." When your police officers are standing near the train station conducting Residence Card checks, what are the professional duties? What law describes this?

どうか説明してもらえませんか。よろしくお願いします。

Thank you for any information you can provide.

The Actual Crime Rate Is Unpublished

An interesting question is what the crime to population ratio is for various countries' citizens living in Japan. Although this is a straightforward question, it's hard to get a precise answer. Wikipedia tells us that in 2010, the national population was 128,057,352 and the foreign population was 2,134,151. That much is simple. The crime rate, though, is hard to count, because there are different ways to count it. Some data ignores minor traffic violations. Some data only includes severe crimes and excludes others, according to how the national government classifies criminal offenses. When looking at crimes committed by foreigners, some data includes visa violations, which by definition doesn't occur to Japanese citizens. Some data is broken down by length of stay in Japan, typically divided into short term visa or long term visa. Well, after sorting through a great many sites looking for precise numbers, I gave up. Before I gave up, I found various numbers suggesting a crime to population ratio of 1.17% for Japanese citizens and either 1.43% or 0.72% for foreigners, depending which numbers I used. The 1.43% figure includes visa violations, and if we suppose those are around ⅓ of the crimes committed and exclude them, we get a low 0.95% figure. Regardless, crimes by foreigners are both low in total number and low as a percent of population.

It should be remarked that the Ministry of Justice certainly has enough data to calculate crime per capita per nationality. They choose not to do so. If we want to have a proper discussion about how dangerous foreigners are, we need that data. But if, as the above armchair calculations suggest, the data shows that foreigners are in fact not particularly criminally-inclined, that's the sort of inconvenient truth that people would rather not examine. Additionally, I believe most non-citizen residents are very cautious regarding the law, because a conviction goes hand-in-hand with losing your visa, which means your life working in Japan is over. Most of us who live here take this seriously.

Stop and Frisk

We should care about the law because it's commonly abused; for example, in "stop and frisk" cases. The other day, the Japan Times posted a Q&A column regarding a non-Japanese man who was harassed by the police in Roppongi, Tokyo. Here are some snippets.

Question: On a recent Sunday at 6:25 p.m. in Roppongi, I was stopped by two police officers for apparently no reason in a clear case of racial discrimination. After showing my ID, the police gave me no explanation relating to any criminal act they suspected me of, and they harassed me. They started touching me, grabbing me and putting their hands on me without my permission. When I declined to cooperate with a bag and body search, I was held captive and refused permission to leave. I was held hostage and interrogated....

We don't have details or a video, so we are left to guess at some of what might have occurred. If possible, one should try to take video of these encounters. I don't mean to blame the man here — he should not have to take video of the police in order to avoid harassment — but it's easier for us to know what happened, and therefore what actions were legal or not, when we have a recording to look at. Also, whereas courts are going to believe police officers over civilians, video is relatively indisputable.

Answer: This sounds like a typical "stop and frisk" case that somehow spiraled out of control. Known in Japanese as shokumu shitsumon, or shokushitsu for short, “stop and frisk” is a common procedure among Japanese police. The rules that apply to this kind of questioning are set down in the Police Duties Execution Act of 1948, but since the clauses of this act are ambiguous and contradictory, there have been a lot of arguments about the legal limits on this kind of behavior, and precedents have been accumulating. In short, the police are permitted to: 1) stop a person for questioning, and, if they try to escape, to seize them (although the officers are not allowed to restrain or arrest them). 2) question them (although they have no obligation to answer these questions). 3) request (but not force) them to accompany the officers to a nearby police station or police box for the questioning. 4) frisk them with or without consent....

So that was what happened in Roppongi the other Sunday.

Police business is a hell of a problem. It’s a good deal like politics. It asks for the highest type of men, and there’s nothing in it to attract the highest type of men. So we have to work with what we get...

— Raymond Chandler, The Lady in the Lake (1943)

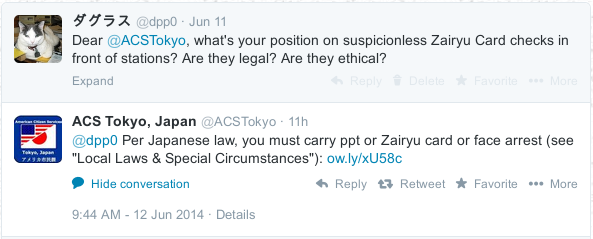

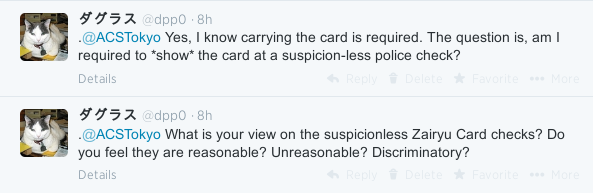

June Twelfth

I contacted American Citizen Services in Tokyo on Twitter to ask them what the think about police forcing suspected foreigners to show ID. Here is the exchange.

First American Citizen Services said only what the Japanese police said: You're required to carry ID. But everyone knows that, and it has nothing to do with the question at hand. Oh well. Their second effort didn't answer my question either, but it was on topic. They pointed to the relevant section of the law and to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Foreign Residents' Advisory Center. I don't know whether the advisory center has substantive knowledge of these matters, but they might. American Citizen Services gave no judgment over the merits or reasonableness of suspicion-less checks. That's not surprising, because they probably want to avoid messing with the Japanese police, but on the other hand, it ought to be the embassy's job to help protect us.

June Eighteenth

Today the seventh graders from my school took a trip to Tsukiji Hongan-ji, a large Buddhist temple in eastern-central Tokyo. On the way, it was my job to stand at the Kayabacho Station and point students in the right direction for changing trains. It's easy to get on the right train the wrong direction there, so I stood around for half an hour and pointed to the right when students came by. Right when I got there, before I started pointing, two plain-clothes police officers came up and asked to see my Zairyu Card, which is a kind of foreign ID card. The same thing happened to me last week, only last week I wasn't on a school outing. As fate would have it, none of my students were around when the cops spoke to me.

There's video of part of the exchange here. This time it was most convenient for me to get video of the time when I ask for his ID, because otherwise I'd forget the details. It would have been better to record the entire affair. Here's a summary.

- I stand at the platform, and two cops start talking to me. One cop walks off.

- I take out my video camera and ask if it's OK to record. The remaining cop says OK and asks to see my ID.

- I ask him his name and to see his police notebook (keisatsu techo). He tells me his name, Sato Mitsunori, and shows me his police notebook, but he says it's not permitted that I shoot video of the police notebook itself. In the video, he tells me his name and I repeat it slowly and clearly. In case the officer is quiet or the location is noisy, it's nice to say the name aloud an extra time.

- I stop taking video and show him my ID. He politely thanks me and goes away.

- About 15 minutes later I walk upstairs to chat with another teacher and see the two policemen there. They apologize for inconveniencing me, and we casually chat for a minute. I ask what they're looking for with the ID checks, and they say they're looking for people overstaying their visas. I ask if that's a big problem, and they say yes, it certainly is, especially with people coming from nearby Asian countries. I ask what police department they work at, and they tell me it's the railway police (Tetsudo Keisatsu), headquartered in Tokyo Station.

- I go back to my place on the platform and subsequently depart as scheduled.

Analysis

These guys were polite and efficient. Mr. Sato, the officer with whom I spoke at length, was nice about insisting on seeing my ID card. He told me his name, showed me his badge number, and told me which branch of the police he works for. Those three things are required by law, if the police want to see your ID. Though the officers were polite, the fact is that their job is disgraceful. First they said that there's a big problem with people overstaying visas. That's not as big a problem as it once was, but maybe there's political pressure to do even better. Then they said it's mostly people from nearby Asia doing so. Not too smart, are they. Really, what kind of chump hassles a white dude about how long he's been in Japan and ten minutes later says the real problem is Asian immigrants? On the other hand, it's hard for the police to know, based on appearance, whether someone is non-Japanese. Instead, they just target the visible minorities, even though their process has thousands of false positives, millions of false negatives, and doesn't accomplish much of anything anyway.

History Matters

According to some researchers at the University of Kansas, a knowledge of discrimination in the past makes it easier for people to identify it in the present. Glenn Adams of the University of Kansas co-authored a recent paper showing the importance of historical knowledge.

In this research ... African-Americans demonstrated more accurate knowledge of historically documented racism in the U.S. than did Americans of European descent. This gap in historical knowledge accounted in part for differing perceptions of racism among these groups, both at a systemic and an incident-specific level. "The remarkable phenomenon is not that people from ethnic and racial minority communities are aware of the history of American racism," said Glenn Adams, associate professor of psychology at KU. "Instead, the remarkable phenomenon is the extent to which people in dominant or mainstream American society manage to remain ignorant of this history."

SB 1070

What the Japanese police don't know is that their actions here are nearly identical the Arizona police under SB 1070, an Arizona law passed and amended in 2010 that was ostensibly intended to cut down on illegal immigration by making it easy for the police to conduct immigration ID checks, but in reality encouraged racial profiling. According to Wikipedia...

U.S. federal law requires all aliens over the age of 14 who remain in the United States for longer than 30 days to register with the U.S. government, and to have registration documents in their possession at all times; violation of this requirement is a federal misdemeanor crime. The Arizona Act additionally made it a state misdemeanor crime for an alien to be in Arizona without carrying the required documents, required that state law enforcement officers attempt to determine an individual's immigration status during a "lawful stop, detention or arrest", or during a "lawful contact" not specific to any activity when there is reasonable suspicion that the individual is an illegal immigrant. The law barred state or local officials or agencies from restricting enforcement of federal immigration laws, and imposed penalties on those sheltering, hiring and transporting unregistered aliens.

I went searching for some stories of people hurt by SB 1070 policing. Here's a snippet from the Huffington Post by Josh Bowman.

Rocky spoke with me about his experience living in Arizona, and how he made the decision to leave after the passing of SB 1070. There were other factors, of course. He moved out to San Francisco with his girlfriend at the time. He wanted a change. What really stuck out for me was Rocky's awareness that life became a lot less safe for him in Phoenix in the summer of 2010. He could be stopped at any time and asked for his papers, and arrested if he did not have proper documentation. He could be harassed on a day to day basis by police with no recourse for justice. The thing is, Rocky is Diné. Also known as Navajo. Also known as Native American. Also known as the first people encountered by European colonialists (also known as our forefathers). Rocky is as far from an illegal immigrant as you can get. Rocky is not an illegal Mexican immigrant, but if by the guidelines of SB 1070 he looked that way to a passing police officer, or if the police had reason to suspect that he is illegal, he could be stopped and potentially arrested.

Here are several snippets from Voxxi by Griselda Nevarez.

Cesar Valdes was driving his younger brother to school last November when a Phoenix police officer stopped him for allegedly driving with an expired license plate. Valdes later confirmed with the Arizona Motor Vehicle Division that it wasn’t expired. The officer cited Valdes for not having a driver’s license and arrested him after he wasn’t able to prove a legal status, as required by Arizona’s new immigration law, commonly known as SB 1070. "He was very aggressive," Valdes said of the officer. "He said 'if you're illegal, we are going to find out and either way you're still going to go to Sheriff Joe’s jail.'" The 21-year-old Dreamer was detained for more than 20 hours until immigration officials verified he was in the process of receiving deportation reprieve and federal work authorization under the new deferred action program for undocumented youth.

One [person] was of a woman who is authorized to be in the United States under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), legislation that gives temporary legal status to undocumented immigrants who are victims of sexual assault or domestic violence. The woman was recently stopped by a Pinal County sheriff and cited for a minor traffic violation. The officer also asked whether she had a lawful status, to which she offered to show a document that proved she is authorized to be in the country under VAWA. The officer refused to look at the document and proceeded to arrest her. She was detained for five days until a domestic violence counselor located her.

[An] undocumented man ... was waiting at a bus stop in Phoenix when another man assaulted him with a knife. The undocumented man fled his attacker but was too afraid to call the police, because he feared he would be questioned about his immigration status.

The aforementioned undocumented man was presumably in the U.S. illegally, but he was more afraid of the police than being assaulted with a knife! Here's another story, this time from the Arizona Daily Star by Perla Trevizo and Carli Brosseau.

In a letter the American Civil Liberties Union sent to South Tucson in November, it alleged that Alejandro Valenzuela — a 23-year-old activist with the Southside Worker Center — was "subjected to unreasonable seizure based on his actual or perceived race and ethnicity" and detained for no reason other than to check his immigration status and to transport him to federal authorities. Police initially talked to Valenzuela when he showed up at a domestic-violence investigation involving one of his friends, and they asked him not to interfere. Officers then asked for his identification while he was sitting in the passenger seat of a nearby parked car. Though they didn’t charge him with a state or local crime, South Tucson police drove Valenzuela first to their offices, then to Border Patrol headquarters.

Pointless Punishment

In both the U.S. and Japan, giving the police greater powers to mess with suspected illegal residents will not solve the problems of illegal immigration and visa violations. In the first place, "suspected illegal immigrant" and "suspected visa violator" are just shorthand for "someone who looks different". In the second place, as long as there are economic incentives to go to a country and work, some people will do so. If one wants to reduce illegal immigration or visa violations, one needs to reduce the systemic incentives, not just increase the punishment on workers. This could be done in part by levying harsh fines on companies themselves. It might also be productive to help other countries stabilize their economies so their citizens could stay at home and make reasonable wages, though that sounds rather challenging. Targeting visible minorities and punishing non-citizens can be politically popular, because it seems like nobody is getting hurt. God damn foreigners come to our country and take our jobs. I been livin' here my whole life and they come in and make a mess of everythin'. Screw 'em. Lock 'em all up, or shoot 'em if you can. This attitude makes no sense at all as it applies to legal labor, since the entire point of a work visa system is that jobs aren't being filled domestically. Even with illegal labor, though, it's harsh and inhumane.

In some cases, punishment for overstaying a visa is doubly perverse. Some companies that employ foreign workers take advantage of the fact that their employees have no recourse if mistreated. Two weeks ago, Reuters published a report showing how many Japanese companies invite Chinese workers to come to Japan under "foreign technical intern" visas but end up as sweat shop workers pulling overtime almost every day and earning far less than the minimum wage. Certainly these workers were not trained as interns, nor were they learning anything technical. What are they to do? They could leave their jobs and try to find new ones. But if they do that, they'll be in Japan illegally, and then they have to worry about the police and getting arrested and thrown in prison or deported, all because their employers are slime. For people in such a situation, strengthening policing powers will only make their lives worse. Reuters spells out exactly how bad things can be...

The most recent government data show there are about 155,000 technical interns in Japan. Nearly 70 percent are from China, where some labor recruiters require payment of bonds worth thousands of dollars to work in Japan. Interns toil in apparel and food factories, on farms and in metal-working shops. In these workplaces, labor abuse is endemic: A 2012 investigation by Japanese labor inspectors found 79 percent of companies that employed interns were violating labor laws. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare said it would use strict measures, including prosecution, toward groups that repeatedly violated the laws or failed to follow its guidance in their treatment of technical interns. Critics say foreign interns have become an exploited source of cheap labor in a country where, despite having the world's most rapidly ageing population, discussion of increased immigration is taboo. The U.S. State Department, in its 2013 Trafficking in Persons report, criticized the program's use of "extortionate contracts", restrictions on interns' movements, and the imposition of heavy fees if workers leave.

The double standard in enforcement on employees compared with employers is striking. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare says that it would enforce the law on companies only if they repeatedly violate labor laws. The Ministry saying that it would enforce the law suggests that it has not yet been enforcing it — otherwise, they'd have said that they already are enforcing it and are considering strengthening measures. And naturally the Ministry hasn't lived up to its word. In a few cases, people mistreated by their employers have won civil suits, but to my knowledge there have been no criminal prosecutions against employers violating employees' rights. Even supposing the Ministry were to keep its word, it would still only be prosecuting repeat offending employers. The police, on the other hand, don't give non-citizens any second chances. If you overstay your visa and get caught by the cops, expect to get thrown out of the country. If you're lucky, you'll have a short stay in an immigration detention center before deportation. If you're unlucky, it'll be a long stay. If you're very unlucky, you'll die. Why is it that companies can break the law many times before regulators might issue a small fine, whereas with individuals, a single visa violation may well lead to deportation? That's entirely backwards from how things ought to be.

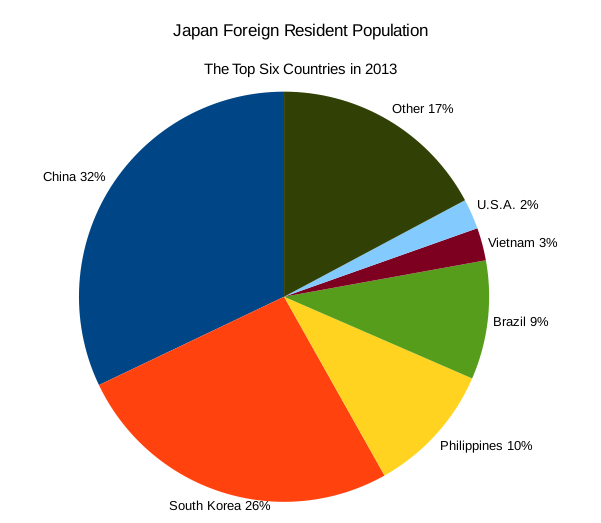

Foreigners Don't Look Foreign

In Japan, like the U.S., you can't look at someone and know if they're a citizen or not. Instead, you make your guess based on visible factors like skin color and hair color. Rather, that's what the police do, and it's ineffective. In Japan, 70% of non-citizens are from Asian countries. Another 9% are Brazilian, typically of Japanese heritage. Only 2% are from the U.S. Probably visa violations are proportional, though there's no easy way to gather such data. By using skin color to guess at nationality, the police are ignoring non-citizens who "look Japanese" and instead targeting all the visible minorities, whether or not they're citizens. This means the police are targeting people based on skin color and not even accomplishing the job they claim they're trying to do, which only goes to show that intelligence is not a prerequisite for discrimination.

You might ask why you should care. After all, many people will never visit Japan. Or Arizona. On the other hand, as the University of Kansas research shows, a knowledge of the history of discrimination helps one identity it in the present. By sharing our experiences, we can become better informed and prepared to tackle these situations as they arise in our own lives. If you live in Japan now, take some time and contact your embassy. Ask them what they think about suspicion-less ID checks, and post the results somewhere public.

Stupid Question Answering

You might ask me that if I'm so upset with Japan, why don't I leave? You might ask that, but you'd be asking a stupid question if you did. I like living in Japan. That doesn't mean it's perfect. Whatever city or state or country you live in, whether it's the place you were born or somewhere you moved, you'll find some bad things. When you find these things, if you have the time and energy, you try to make them better, don't you? I think you should.

July Seventh

The other day I went to the coffee shop, drafted a letter to Ambassador Kennedy, and was walking home when a police officer came up and started talking to me in English. Unlike the previous two times in the past month, he didn't ask for my Residence Card. Instead, Mr. Isobe asked me some questions about where I work and how long I've been in Japan. The conversation is mostly pointless. See the video here. The date was Monday June 30, the time was around 3PM, and the location was just outside the north exit of Musashisakai Station, which means the police officer is employed by the Musashino Police Department (武蔵野警察署).

You might ask what the heck the cop wanted. Did he want to speak with me to see if I was suspicious? But then why didn't he ask for my Residence Card as other cops have in the past? I prefer not having my ID checked, but it's nevertheless bizarre. Meghan speculated that maybe a supervisor in the Musashino Police Department decided that police should practice their English conversation skills in preparation for the 2020 Olympic games that are to be held here in Tokyo. You can see how someone sitting at a desk might think that makes sense. Never mind the fact that it's still racial profiling, and it still makes the general public fear foreign looking people, because they're regularly questioned by the police and are therefore suspicious and therefore criminals. Also, if the cops want to practice speaking English, they should hire English teachers just like everyone else does. I don't know what the deal is, but that's what happened last Monday.

Letter to the U.S. Embassy

To: Ambassador Caroline Kennedy U.S. Embassy in Japan 1-10-5 Akasaka Minato-ku, Tokyo 107-8420 JAPAN Phone: 03-3224-5000

Dear Ambassador Caroline Bouvier Kennedy,

Seeing as you are the United States Ambassador to Japan, I would like to ask several questions regarding police treatment of non-Japanese residents in Japan, including approximately fifty thousand American citizens.

You may be aware that the Japanese police claim legal authority to require non-citizens living in Japan to show ID upon request. They base this authority under the law as stated in Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act, under Chapter IV Section 2 Article 23. Police officers wait in or near train stations, and when they see someone who "looks foreign" — typically based on skin color — the police demand to see that person's passport or Residence Card, even if the person is behaving entirely normally. By intention, these police checkpoints target visible minorities, which includes a significant percent of Americans visiting or residing in Japan. This problem has been clearly documented.

- http://www.debito.org/?p=12138

- http://www.mutantfrog.com/2010/05/03/france-china-arizona-and-narita-all-want-to-see-your-papers/

Does the Embassy feel the suspicion-less checkpoints are reasonable? Does the Embassy feel the suspicion-less checkpoints are discriminatory? Does the Embassy feel the suspicion-less checkpoints are an example of racial profiling, and if so, how does the Embassy feel about that? Has the Embassy consulted with the National Police Agency about these checkpoints in any fashion? Does the Embassy currently have any plans to do so?

These checkpoints are harmful. The police can harass anyone who "looks foreign" any time they like. That is bad for the people who get harassed. Moreover, other people observing these checkpoints have no idea that those targeted are completely innocent. People see the police questioning a person, and they tend to assume that person is suspicious.

Americans living in Japan should not be mistreated just because we are not Japanese citizens. We work steady jobs, have proper visas, pay taxes, and obey the law. It is the U.S. Embassy's job to support us with regards to affairs like this one. Will you take action to support us on this issue?

Sincerely,

Douglas Paul Perkins

The Embassy's Reply

The Embassy replied and gave me a list of attorneys. I hadn't expected to get an answer at all, and this one was relatively polite and somewhat informative. Still, in my letter to them I asked some questions that were not answered.

- Does the Embassy feel the suspicion-less checkpoints are reasonable? They do not say. They don't even say if you are required by law to show ID at the checkpoints. They say "any person may be taken in for questioning if that person does not have a passport or Japanese residence card to show identity and visa status". What does that mean? Lots of things may happen. I might agree to go to the police station for questioning, so the sentence is technically true. And we all agree that in some situations, like when you're getting your visa renewed, when you enter or leave the country, and probably if you get arrested, you need to show ID. That is not interesting. What we want to talk about is compulsory suspicion-less ID checks, such as those found at or in front of train stations, not optional scenarios that may occur or other situations where it's self-evident you'd have to show ID. The Embassy's wording here is ambiguous and consequently their statement lacks substantive meaning.

- Does the Embassy feel the suspicion-less checkpoints are discriminatory? They don't say.

- Does the Embassy feel the suspicion-less checkpoints are an example of racial profiling, and if so, how does the Embassy feel about that? They don't say. Nothing in the letter indicates they understand the distinction between being foreign and looking foreign, so perhaps not.

- Has the Embassy consulted with the National Police Agency about these checkpoints in any fashion? They don't say.

- Does the Embassy currently have any plans to do so? They don't say.

- Will you take action to support us on this issue? They say no, but if I get arrested, then they'll look into the situation. Well, that's better than nothing, but not by a lot. If you get arrested, what are the odds of keeping your job, your visa, and successfully renewing your visa when it expires? Low.

Those of us who live and work in Japan can't risk getting arrested just to see if the Embassy will support us — we want to see real Embassy action now in the hopes that, among other things, it will help prevent people from getting arrested in the future. Regrettably, Mr. Gardner does not show an interest in preventative diplomacy. That might make his life and job easier, but the rest of us are worse off.

My Second Letter

Being unsatisfied with the embassy's response, I drafted and sent a second letter.

To: Ambassador Caroline Kennedy U.S. Embassy in Japan 1-10-5 Akasaka Minato-ku, Tokyo 107-8420 JAPAN http://japan.usembassy.gov/contact.html Phone: 03-3224-5000

Dear Ambassador Caroline Bouvier Kennedy,

I wrote to you two months ago (2014-06-30) about the way Japanese police conduct ID checks on American citizens visiting and living in Japan, even when we have done nothing to warrant suspicion. A month ago (2014-07-29), I received a reply from Gregory Gardner, Chief of American Citizen Services. Thank you to you and your staff for responding. Mr. Gardner included a link to a list of attorneys, which would be useful should I need one. Regrettably, Mr. Gardner's letter contained many factual errors.

In your letter you express concern about demands by Japanese authorities to see either passports or other official identification from non-citizens. In your letter you state that Japanese officials establish identification checkpoints in public locations, and express concern that police intentionally target foreigners. Americans traveling in Japan are subject to Japanese laws, and these laws can be vastly different than our own. Consequently, Americans in Japan may find their interactions with local police different from what they may expect from authorities in the United States.

— Gregory Gardner, Chief of American Citizen Services (2014-07-29).

First of all, why is Mr. Gardner focusing on people traveling in Japan? I emphasized the status of "non-Japanese residents in Japan, including approximately fifty thousand American citizens." Second, Mr. Gardner has no idea what I know about Japanese law. His words come across as presumptuous and insulting. Third, contrary to Mr. Gardner's claim, immigration law in the U.S. and Japan are similar in many ways. There are obvious parallels between Arizona's SB 1070 and the issues I mentioned.

Mr. Gardner wrote I express concern that "police intentionally target foreigners". He is mistaken. I wrote that the police target visible minorities, which includes many foreigners.

Police officers wait in or near train stations, and when they see someone who "looks foreign" — typically based on skin color — the police demand to see that person's passport or Residence Card, even if the person is behaving entirely normally. By intention, these police checkpoints target visible minorities, which includes a significant percent of Americans visiting or residing in Japan. This problem has been clearly documented.

— Douglas Perkins, Letter to the Embassy (2014-06-30).

In my letter I tried to ask about the discriminatory nature of ID checkpoints and ID checking by the Japanese police. You can't tell if a person is a citizen or not just by looking at them, so the police rely on visual cues, such as race. When they stop me and ask to see my ID, it's only because I don't "look Japanese". Hassling people because of their skin color is not acceptable behavior for anyone, and certainly not for police officers. I hope to see the Embassy make a public statement to this effect.

Sadly, the Japanese police have a history of arresting Japanese citizens who "look foreign" on suspicion of being foreigners and not carrying their (non-existent) immigration documents with them. On August 13, a Filipino-Japanese man was arrested and held for twelve hours before the police realized their mistake and released him with a brief apology. We can easily imagine seeing the same thing happening to someone of dual American-Japanese citizenship. What will the Embassy do? You won't be able to say you didn't see it coming. Preventative action seems like a good idea.

Around noon on Aug. 13, in Ushiku, Ibaraki Prefecture, a local apartment manager notified the police that a "suspicious foreigner" was hanging around the nearby JR train station. Police officers duly descended upon someone described by the Asahi Shimbun as a "20-year-old male who came from the Philippines with a Japanese passport." When asked what he was doing, he said he was meeting friends. When asked his nationality, he mentioned his dual citizenship. Unfortunately, he carried no proof of that. So far, nothing illegal here: Carrying identification at all times is not legally required for Japanese citizens. However, it is for non-Japanese. So the cops, convinced that he was really a non-Japanese man, took him in for questioning — for five hours. Then they arrested him under the Immigration Control Act for, according to a Nikkei report, not carrying his passport, and interrogated him for another seven. In the wee hours of Aug. 14, after ascertaining that his father is Japanese and mother foreign, he was released with verbal apologies.

— Debito Arudo, The Japan Times (2014-09-03).

Moreover, even if the Japanese police insist on conducting race-based ID checks, they could still do so less frequently. Just the other day, and for the fourth time in four months, the police here in Tokyo stopped me and asked to see my Residence Card. I went six years in Japan with only two ID checks, and now we're up to double that in four months! It's ridiculous. Any time the police ask to see my Residence Card, there's an element of risk. There are at least a dozen possible ways an ID check could go badly. Though I expect it will be many years before Japanese law is amended to forbid discrimination based on race, political pressure from the U.S. Embassy now could go a long way to reducing the numbers of these police checkpoints. External pressure (in Japanese, "gaiatsu") plays a critical role in shaping public policy in Japan regarding discrimination. American citizens living here hope to see the Embassy to step up and support us in a broad open and public fashion. Won't you do so?

Sincerely,

Douglas Paul Perkins

September 8, 2014

Politicians remark, that no oppression is so heavy or lasting as that which is inflicted by the perversion and exorbitance of legal authority. The robber may be seized, and the invader repelled, whenever they are found; they who pretend no right but that of force, may by force be punished or suppressed. But when plunder bears the name of impost, and murder is perpetrated by a judicial sentence, fortitude is intimidated, and wisdom confounded: resistance shrinks from an alliance with rebellion, and the villain remains secure in the robes of the magistrate.

— Samuel Johnson, The Rambler No. 148 (1751).

September Fifth

Police questioning is getting excessive. Yesterday, the cops checked my ID when I was walking from school to Kichijoji in the middle of a residential neighborhood, Sekimae 3-chome. This is the fourth time since late May. Maybe you'll get arrested if you don't show ID. But you don't have to like it, and you can certainly take video of the whole thing. Here's my video, which was cut off when I accidentally pressed the side of the touch screen.

Though I spend as much time in Nishitokyo as I do Musashino, the police in Nishitokyo have never asked to see my ID. This suggests the Musashino Police Department is making a targeted effort against illegal immigration. It could just be bad luck, but the odds are against that.

To whom much is given much is tested

Get arrested guess until he get the message

I feel the pressure, under more scrutiny

And what I do? Act more stupidly

...

Excuse me? Was you saying something?

Uh uh, you can't tell me nothing

You can't tell me nothing

Uh uh, you can't tell me nothing

— Kanye West, Can't Tell Me Nothing (2007)

A Police Officer's View

This morning, I stopped by the neighborhood police box in Nishitokyo and asked the officer there what he thought about being questioned four times in four months. He said that it was probably just bad luck. He was quick to ask if it was always different police officers, or if any of them had been the same. He said that if the same officer asks multiple times — which didn't happen to me — I should certainly document it and complain to the officer's police station. For example, I walk by the neighborhood police box on the way to work, so this officer knows who I am. Therefore he has no reason to see my ID multiple times, and if he insists on it, he could be reprimanded. Other than that, he said there was no recent immigration law enforcement policy change. I assume he's telling the truth — he seems like a reasonable guy, and what's the point in lying, anyway. Still, he's a member of the Tanashi Police Department, and three of the above four incidents involved the neighboring Musashino Police Department. This suggests department-specific factors involved in the recent escalation of ID checks.

Questions for Police

On March 15, 2015, I sent a letter to the Musashino Police Department with many questions about the way they enforce immigration law, and in particular with the way they check immigration documents when people are walking around in public. I don't like the law and their conduct, but it won't change just because I don't like it. What I can do, and what you can do, is gather data on how police departments around Japan conduct their ID checks. The first step is to always take video of police interactions and share that video publicly. The second step is to write letters to police departments asking them about their policies. This latter step is one I intend to pursue in greater detail. Let's create a template for a letter that anyone in Japan can modify and send to their local police department to request information about immigration law and enforcement data. Because many non-citizens have limited Japanese ability, we need a letter written side-by-side in English and Japanese.

Police departments may or may not reply to letters you send them. Even if they reply, they may or may not provide data you request from them. But accountability starts with inquiry. Police departments that repeatedly ignore communication and information requests from local taxpayers are self-evidently non-responsive and irresponsible. If even a few Japanese police stations provide comprehensive answers to open inquiries, all other police departments will be embarrassed and lose face if they refuse to do the same. Once we have data on how police departments enforce immigration law, we can have an informed public discussion on whether police actions are reasonable or effective.

| English | 日本語 |

|---|---|

| Dear Musashino Police Department Chief, | 武蔵野警察署長 |

| My name is Douglas Perkins. I live in Tokyo and often go to Musashino City. | 私はダグラス・パーキンスです。私は東京に住んでいます。武蔵野市へよく行きます。 |

| I have some questions for the Musashino Police Department regarding immigration law. I would like to learn more about how the department enforces the law. If you can provide some data from last year, that would be very helpful. | 移民法に関して武蔵野警察署の警察官の行動ですが、質問いくつあります。移民法の実施にあたり、貴所ではどのような措置や対応を行っていますか。状況を知りたいのですが、後述の内容について2014年のデータを提供していただくことは可能ですか。よろしくお願いします。 |

| In 2014, how many times did your officers ask to see someone's passport or Residence Card? What were these people's countries of citizenship? | 2014年に、貴所がパスポートまたは在留カードの呈示を求めた通行人の合計人数と、(身分証明の呈示により判明した)国籍を教えていただけますか。 |

| For the above people, how many of them did not have their passport or residence card? What were these people's countries of citizenship? | そのうち、パスポートも在留カードも所持していなかった人の人数と、その国籍を教えていただけますか。 |

| For the above people, how many of them were Japanese citizens? | そのうち、日本国籍を保有していた人の人数を教えていただけますか。 |

| For the above people, how many of them were arrested for failure to carry their passport or residence card? What were their countries of citizenship? | そのうち、パスポートも在留カードも所持していなかったという理由で逮捕された人はいましたか。その人数と国籍を教えていただけますか。 |

| For the above people, how many of them were warned but not arrested for failure to carry their passport or residence card? What were their countries of citizenship? | そのうち、逮捕はされなかったが、身分証を携帯するように警告を受けた人の人数と国籍を教えていただけますか。 |

| Officers from your department have asked to see my ID when I've been walking down the street and walking through the train station. These officers wanted to see my residence card even though I was not engaged in suspicious activity. I have some questions about your officers' targeting people who are entirely suspicion-less. | 私は散歩中または駅前を通行中に、貴所の警察官により在留カードの呈示を求められたことが去年複数回ありました。私は何も怪しいことをしていなかったにもかからわず、在留カードを見せなければなりませんでした。少なくともなぜ在留カードを見せなければならなかったのか、納得するに足りる説明は受けておりません。このような「疑うに足りる相当な理由」がなかった状況について、いくつか質問があります。 |

| In 2014, how many times did your officers ask to see a person's passport or residence card, even though that person was not doing anything suspicious? What were these people's countries of citizenship? | 2014年に、貴所の警察官が、このような(何らかの違法行為や違反行為を犯そうとしていると)疑うに足りる相当な理由がない状況で、通行人のパスポートまたは在留カードの呈示を求めるという事態が発生した回数と、その通行人の国籍を教えていただけますか。 |

| For the above people, how many of them did not have their passport or residence card? What were these people's countries of citizenship? | 前述の状況でパスポートまたは在留カードの呈示を求められた通行人のうち、パスポートも在留カードも所持していなかった通行人の人数と、その国籍を教えていただけますか。 |

| For the above people, how many of them were Japanese citizens? | そのうち、日本国籍を保有していた通行人の人数を教えていただけますか。 |

| For the above people, how many of them were arrested for failure to carry their passport or residence card? What were their countries of citizenship? | そのうち、パスポートも在留カードも所持していなかったという理由により逮捕された通行人の人数と、その国籍を教えていただけますか。 |

| For the above people, how many of them were warned but not arrested for failure to carry their passport or residence card? What were their countries of citizenship? | そのうち、逮捕はされなかったが、警告を受けた通行人の人数と、その国籍を教えていただけますか。 |

| I am eagerly awaiting your response and the above information. Thank you very much. | ご多忙のところ恐縮ですが、ご回答をお待ちしております。どうぞよろしくお願い申し上げます。 |

Reply from the Police Chief

| 日本語 | English |

|---|---|

| 平成27年3月24日 | 2015-03-24 |

| ダグラス・パーキンス殿 | To Mr. Perkins |

| 警察庁武蔵野警察署 | Musashino Police Department |

| 警備課長 中山 祐二 | From Section Chief Nakayama |

| 2015年3月13日付当署宛の文書については下記のとおり回答します。 | We received a letter from you on March 13, 2015. Here is our reply. |

| 記 | Record |

| 要望内容にあります各種データについては、当署において統計を取っておりませんのでお答えすることができません。 | The data that you have requested involves statistics that we do not collect at this police station, so we cannot provide it to you. |

| 今後も法令に則って適正に職務に精励してまいりますので、引き続き警察へのご理解、ご協力をよろしくお願いいたします。 | We will continue to diligently enforce the laws. Thank you for your cooperation. |

The local police department likes to send its officers out to hassle foreign-looking people because, they say, some of us might be in the country illegally. But when asked for data on effectiveness, they don't have any. That's crazy, right? The cops are supposed to keep us safe. That's why we give them badges and guns and cars with lights. They go out, they patrol, they reduce crime, and they catch the lawbreakers. Except here they aren't doing that! There is no law that requires the cops to screw with me — they want to screw with me. Why? We don't know. There are probably many reasons, but none of them have the effect of reducing illegal immigration.

For entertainment, let us speculate on what the numbers that the cops don't collect might be and what that might indicate.

Probably the Musashino Police Department arrested very few or no people for visa violations last year. If they had arrested many people, I probably would have noticed the news. Assume they arrested almost nobody. Then however much they were checking could be reduced by 80% or 90% or and have the same effect. Why would you waste time searching for lawbreakers that don't exist? It's a waste of resources and doesn't reduce crime.

Contrarily, suppose the Musashino Police Department arrested a bunch of people last year. If so, then we'd find out their nationalities if there were data available. What that data might show is relatively large numbers of people from non-Asian countries getting arrested. Assuming actual violators are proportional in number to resident nationality population, you would expect 55% of them to hold Chinese or South Korean passports. This is an oversimplification; the real numbers surely vary more than that because people in lower-level jobs are more likely to be stuck without legal employment, and income is not distributed evenly by nationality. Regardless, it sucks for those poor cops who are stuck using racial profiling to distinguish Chinese and Korean from Japanese. And if they get it wrong and accidentally arrest a Japanese citizen for breaking immigration law, it's horribly embarrassing. Better to just fuck with the visible minorities instead.

Or suppose that miraculously there were real numbers of arrests and those were proportional to resident nationality population. I don't think we'd find that pattern emerging, but if we did, we can roll with it. Then we would immediately ask how these people got into the country, who they were working for illegally, and why they left legal jobs, assuming that in the past they had them. The police would be obligated to investigate their employers. Can you imagine that? I can't. But it would be interesting to see.

It shouldn't need to be said, but here's how good public policy management occurs... You find a problem, and you measure it. You consider several solutions and adopt one. You keep gathering data, and after a year or five, you analyze the data. If the solution you adopted was a good one, the problem has gotten better, you brag about it, and everyone is happy. That's what the cops should be doing. That's what the cops aren't doing, and it's a clear failure in leadership.

I try to play my music

They say my music's too loud

I tried talkin' about it

I got the big run around

And when I rolled with the punches

I got knocked on the ground

By all this bullshit going down

Time is truly wastin'

There's no guarantee

Smile's in the makin'

You gotta fight the powers that be

— The Isley Brothers. Fight the Power (Part 1 & 2), 1975.